Disclaimer: The below does not constitute investment advice. Please do you own research or obtain your own advice. The views presented are my own. I do not own GoPro or Blackberry shares at the current time, but am watching them closely. I also don’t own Costco. I will update this disclosure if I buy any of these stocks.

My professional life requires me to invest in the private markets. I’m lucky to do something for work that I really love (investing) – but I digress. Recently, I was presented an opportunity to invest in a venture backed company at a reasonable valuation with a strong growth profile, and above average unit economics. Despite this, I was immediately negatively disposed to the investment. The issue I encountered was that this business operated in a sector which was heavily out of favour, investors in the past had lost substantial amounts of capital, and while this business had a subscription model it wasn’t B2B SaaS (think B2C, lower gross margins and much higher churn). A number of investors have pulled out of the sector, and therein was the opportunity to invest in a business with strong underlying fundamentals at a reasonable valuation.

My initial negative inclination was anchored by my experience in watching a most of the other companies in the sector either:

Go out of business

Be acquired for less than they raised from investors, leaving investors with pennies on the dollar in terms of their return – so basically went out of business

Listed but experienced material declines in their stock price

It wasn’t until a peer called me out on it. He noted despite the obvious merits of the investment, I was still a hard pass. Where was the logic? There was none.1

I had just experienced the impact of anchoring bias and how it affected my decision as a professional investor. Not a moment I am proud of, but certainly one I will learn from.

Other examples of anchoring bias in an investing context that you may not have considered include:

You decide not to sell your investment property as you think house prices in Sydney will continue to go up.

A stock hits $50, and you don’t sell. The stock drops to $40 which represents its intrinsic value but you are unable to sell the stock as you’ve anchored yourself to the $50 price.

A company upgrades its earnings outlook but investors remain skeptical given a history of underperformance

Investors have a view on a particular company and what it does….even if that was the case

Anchoring bias is dangerous. It means as an investor we throw out objectivity and rationalism to satisfy our brains desire to get to the answer that “feels” right even where the facts don’t support it.

We’re all shaped by our experiences. The ability to be aware of “anchors” when assessing an opportunity is one factor that (in my view) separates average and great investors.

That’s not to say great investors get it right all the time. Take Buffett and Munger and their decision not to invest in Google on the basis they didn’t understand technology. Both openly admit that they missed Google. Around the time of Google’s IPO, Berkshire’s subsidiary GEICO was paying Google $10 a click and despite observing this and understanding the value Google was bringing, they decided to pass. That would prove to be a costly mistake, as Berkshire passed up the opportunity to invest in the company at its IPO and missed out on a ~5000% return. As Munger said at the Berkshire 2019 shareholder meeting:

"We could see in our own operations how well that Google advertising was working, And we just sat there sucking our thumbs."

"I feel like a horse's ass for not identifying Google, I think Warren feels the same way. We screwed up."

Warren helpfully translated:

"He's saying, we blew it.”

Despite seeing the opportunity, and understanding the business model, they were anchored by their views that technology was not in their circle of competency.2

Overcoming anchoring bias

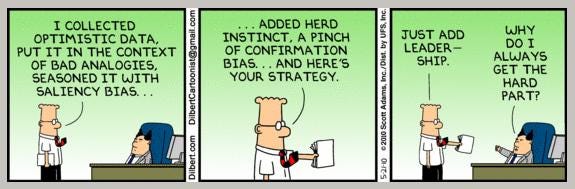

Daniel Kahneman, talks about anchoring bias in Thinking Fast and Slow. As humans we naturally want to take mental short cuts – and this where anchoring bias comes from. The simple solution is not to take short cuts, and make sure the investment thesis you are presenting is driven by a strong fact driven due diligence process. Over time, I think investors should track their decisions to identify if there are reoccurring patterns (or anchors) that effect their investment decisions. I (for example) have traditionally had an anchor to growth businesses with SaaS like characteristics - its meant I’ve missed out investing in great businesses like Costco ($COST). I’m trying to make sure that doesn’t happen again.

There is a secondary purpose to this article. I’ve spent the last few weeks digging into and building conviction in two companies that I’ve historically disregarded, Blackberry ($BB) and GoPro ($GPRO) - both of which sit squarely in the last example I noted above (Investors have a view on a particular company and what it does….even if that was the case ). More on those two stocks in another post but don’t be surprised if I initiate a position in the near term.

For the record, I ended up declining to invest. But there were other reasons which led me to this decision.

To be clear, I’m not disparaging them for sticking to their circle of competence. One of the reasons Charlie and Warren have been so successful is their relentless discipline. I’m just trying to demonstrate that even the best and ,most rationale investors can let their anchors dissuade them from making an investment - even where the facts present an alternative reality.

Exploring the correlation of various cognitive biases and investing is sort of brilliant!